Commentary by Jonathan Matthes

Darkness blanketed a sleepy Vermont the night word of President Warren Harding’s death arrived. A messenger was sent; a father answered the door, then ambled upstairs to alert his slumbering son and daughter-in-law. Calvin Coolidge, the vice president of the United States, wiped sleep from his eyes and headed downstairs. By 2:24 a.m., with some hastily assembled journalists on hand, a Bible and a copy of the U.S. Constitution were ready. The father was a justice of the peace. Then, by candlelight, the father administered the oath of office to his son.

Upon hearing the news, prominent Senator Henry Cabot Lodge spoke the shock felt by many, “My God! That means Coolidge is president!”

Coolidge’s own reaction was, true to form, less demonstrative. He headed upstairs and went back to sleep. Coolidge was awakened early on the morning of Aug. 2, 1923 as a vacationing vice president. He returned to bed a couple hours later as the 30th the president of the United States.

Coolidge has left a legacy that can be interpreted in many different ways.

During his own time, he was popular. Not long after he left office, he was cast in a dour light. Critics claimed his lack of progressive economic policies helped facilitate the Great Depression. During the Reagan presidency, Coolidge’s reputation saw a resurgence. Not only was the Depression not his fault, but Coolidge showed how America could prosper under conservative principles.

I didn’t care about any of that.

I became drawn to Coolidge through the charm of his silence.

I’m not alone. Many during his time found ‘Silent Cal’s’ judicious use of words comforting.

While boarding a plane to leave Wisconsin, a reporter asked President Coolidge if he had anything he wanted to say to the people of Wisconsin before he left. Coolidge replied, “Goodbye.” Then he boarded the plane and went back to Washington.

See what I mean?

There’s something refreshing about him. Maybe it’s because we are so consumed by words. Turn on a news channel and we see words being shouted at one analyst by another. Words constantly scroll across the bottom of our Colts’ games. They pop up on our phones in messages of 140 characters or less. They even cover our Instagram posts, an app dedicated to pictures. Words are everywhere.

And then there is Calvin Coolidge.

Grace Coolidge, Calvin’s wife, found her passion working with deaf children. When a friend heard that she was engaged to Coolidge, he remarked. “Grace teaches the deaf to hear, now we’ll see if she can teach the mute to speak.”

Coolidge was president during the Roaring Twenties, a time like today, where excitement was booming. The world was getting smaller. Airplanes flew in the sky, radio could broadcast a voice over an entire region, people could go to movie houses and watch Charlie Chaplin films. America was no longer the quaint land of the citizen-farmer that Thomas Jefferson dreamed of. America was reveling in post-World War I victory, oblivous to the problems of another war, depression and genocide that were on the horizon.

Coolidge seemed out of place, a man that wasn’t ready for a faster-paced world. On a related note, he was afraid of automobiles and was once nicked by one while he tried to cross the street.

After an era of progressive presidents, Coolidge was fond of saying that it was time to let administration catch up with legislation. And under Coolidge, it did.

Coolidge’s big focus was the budget furing his presidency. Unemployment hovered between 3 and 5 percent. The national debt actually decreased, and the nation ran a surplus. All three of those happened each and every year when he was in office. He also reeled in the spending of Washington, shrinking the size of the federal government. It was smaller when he left office than when he entered it.

He was the Roaring Twenties’ Jiminy Cricket, if Jiminy Cricket never sang.

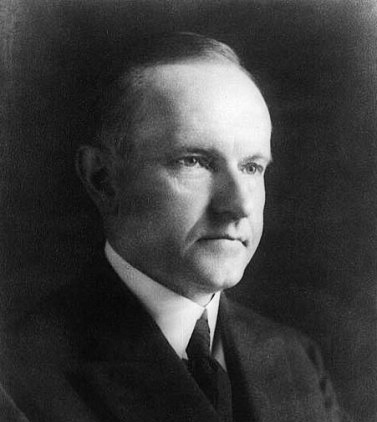

Contrary to his reputation for silence, Coolidge was a pretty visible president. His picture was taken so often that he was once called the most photographed man in the world. In most pictures he either looks pleasant or mildly annoyed, like a man sharing an elevator with two 13-year-olds that just pressed all the buttons between the ground floor and top because it looked like a Christmas tree.

There was a sadness to Coolidge, as well. His two sons liked to play tennis together on the White House tennis courts. One day Coolidge’s favorite of the two, Calvin Jr., didn’t show up to play with his brother. Calvin Jr. had developed a blister on his foot, which became infected. He would later die from blood poisoning. The boy was 16.

Coolidge was devastated. With his son’s death, every joy of the presidency died, too. He slept more, his temper shortened and his typical silence became more somber. When he decided not to run for reelection in 1928, Coolidge was in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Imagine how a president would normally announce that he was not seeking reelection.

Coolidge said, “I do not choose to run for president in 1928.”

That’s the whole quote.

A reporter quickly found Coolidge’s wife, who was back in Washington, and asked her what she thought of the announcement. “What announcement?” she asked. Coolidge hadn’t told her about it beforehand. In fact, he never would elaborate on his decision. He just didn’t want to be president anymore.

To close, let’s talk of a happier time.

A popular saying at the time was, “Washington is first in war, first in peace and last in the American League.” The Washington Senators were the hometown baseball team, and they had spent their entire history being terrible at baseball. They even had one of the greatest pitchers of all time and they still stunk.

But a miracle happened in 1924. The Senators were good. Wait, they weren’t just good, they were really good. Hold on, they could make it to the World Series! Oh my heavens, the won! The horrible Senators caught lightning in a bottle and beat the New York Giants, in seven games, to win the 1924 World Series.

Washington was bedlam. Nobody knew what to do. Residents flooded the streets, poured into the national mall and gave the Senators a hero’s parade. Tears seeped from the eyes of Walter Johnson, the great pitcher. And in the midst of the jubilation was the President of the United States, Calvin Coolidge. You might wonder how would a president react during such a raucous occasion? A newspaper recorded how Coolidge reacted.

His vocal cords twitched.

Say no more, Cal. We hear you loud and clear.

Special thanks for sourcing to: David Rodgers, Zionsville Community High School; Amity Shlaes: Coolidge; Thomas Mellon and The New Yorker, “Less Said”; The Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia; Lillian Cunningham, The Washington Post: “Presidential” Podcast; and Matthew Solyntjes, Diocese of Sioux City