Commentary by Fred Swift

Recently WFYI-TV aired a re-run of a program called “Indy in the Fifties” which is an interesting look back at everyday life in the 1950s. As I watched, I thought of how we had our own history in Carmel during the 50s. From a young person’s view at the time, I thought memories of the time might be of interest to those who cannot visualize Carmel as a small town, as well as those who were here to experience that era.

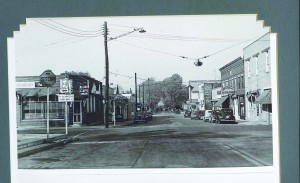

As the 1950s dawned, Carmel was a tight-knit community of just more than 1,000 residents, and the population did not increase dramatically during the decade. By the end of the 50s, the population was still only 1,500 although surrounding Clay Township was beginning to grow rapidly. There was a good chance that every Carmelite would often see every fellow citizen since there was only one school, one drugstore, one bank, three churches, two or three gas stations and two grocery stores. And, there was one single-screen movie theatre appropriately named Carmel Theatre, popular with the younger generation from Carmel and surrounding areas. It was owned by Harry Jones, a retired dentist who lived two doors from the movie house in the first block of South Range Line Road.

Doc Jones hired a family, Jack and Gladys Ford and son, Louis, to run the place. They sold the tickets, the refreshments, showed the film and maintained discipline. Gladys was not bashful about walking the aisles and removing a loud or unruly teenager if the need arose. Doc Jones was often present as a greeter. He was known to refuse to show a movie because he didn’t think it was suitable for his Carmel audience, and he refused to increase his 50-cent admission when film distributors thought he should do so.

There was often chatter at school on Monday about who had been seen with whom at the movie, or who had been ushered out by Gladys. School was a 12-grade, three level structure on East Main Street where a newer portion of Carmel High School now stands. (The first section of the present high school was built in 1958 for $1.5 million. Nearly half the cost went for a 4,400-seat gym when enrollment was nearing 400.

In the old building, grades one through six were found on the main floor, seven through 12 had classes in the top and bottom levels. The cafeteria, home ec and science departments were in a separate, smaller building to the west. In the mid-50s the school was headed by principal Olin Swinney. The school had an almost mandatory weekly chapel service for high schoolers. Protestants went to the auditorium and Catholics to the study hall. Almost no one refused to attend, and there was never a question about separation of church and state that I remember.

The school was crowded, informal and offered few courses beyond the basics. The foreign language department, for example, had two teachers and offered Latin every year, and Spanish and French only in alternating years. Most seemed to enjoy their school experience. Students knew all classmates, and teachers knew all students. My class had 85 members. The kids were not totally innocent, but drugs and hard rock were unknown to them. There were pranks that now and then went a bit too far.

One night in 1956 while Principal Swinney and his wife were entertaining guests at their home, someone painted the guests’ car from bumper to bumper with blue house paint. On Monday morning a furious Mr. Swinney called a convocation of all 175 or so CHS male students. He informed us that the guilty party would either confess by noon or the State Police would come the next day to administer lie detector tests to all. Poor Mr. Swinney learned later that he had the wrong suspects. It was a girls’ slumber party group that painted the car.

Secrets were hard to keep in 1950s Carmel. You certainly did not want to try to have a private conversation on the telephone. The phones were all a party line system. And, it wasn’t touchtone or dial. If you lifted the receiver, an operator came on saying “number please.” Picking up the phone to listen while your neighbor was talking was common. And, word traveled fast. But the system had its advantages. If you heard a fire truck in the area or you missed the high school score, you just asked one of the operators. They seemed to know everything. My next door neighbor was an operator, so I learned a lot of things, too. But, in 1956 dial phones came to Carmel thus ending an era.

Leading and shaping the community during the decade were such folks as Marcus Kendall, Rue Hinshaw, Phil Correll, Martha Ferrin, Minnie Doane, Leroy New, John Morris and Avriel Shull. These were folks who made things happen in Carmel. They’re all gone now, but they helped prepare and shape the community and its institutions for the decades of tremendous growth to follow.

Municipal services in Carmel in the 50s were limited. There was only one policeman, Marvie Myers. When he went off duty at night, it was no secret. His car could usually be seen parked beside his home. Marvie was a good guy. Carmel experimented with parking meters briefly in the late 50s. If he recognized your car, Marvie would put a couple of pennies in the meter for you if it had expired, and mention to you later that you needed to watch your time a little closer.

The fire department gradually took on a handful of paid firefighters during the decade, but was always backed up by number of volunteers. When there was a fire, a siren atop the station on First Avenue SW sounded and the volunteers came running. The siren also sounded at noon and 10 p.m. I was never sure why.

The only park in the area was the privately owned Northern Beach which had a pool. It was a great pool because a portion of it was shaded by large trees. The pool and park had a sign of the times at the gate. It read: White Patrons Only. But, that was the only tangible evidence of prejudice I ever saw in Carmel.

Mass transit of which we hear so much today, came in the form of the Sheridan Bus Line. The privately owned service from Sheridan to downtown Indianapolis stopped anywhere, anytime to pick up anyone along the route. In bad weather Brown’s Drugstore on North Range Line served as the local bus station.

The drugstore, owned and operated by John Brown, also served as a downtown social center. At the counter and a few tables, locals would gather for coffee and conversation in the morning. Store owners and workers would come at lunchtime, and teenagers would congregate after school. One of the drugstore regulars was John “Two Gun” Brunson. He was Carmel’s trash man long before Waste Management or the others came to town. John would pick up your trash for $3 a month. He picked up litter on the streets for free. John’s personal appearance was not appealing, and his language was not polished, but he was a good citizen who performed a needed service and did it well. At the drugstore it was not unusual to see the bank president, the barber, a fireman and Two Gun all talking together. In other words, everyone socialized pretty freely regardless of their position.

The drugstore, the movie theatre and the old high school are among the landmarks that are long gone. Other destinations no longer with us include such places as the Block Mansion and Northwood Drive-in. Groups of youngsters used to get a kick out of driving out to the vacant former summer home of the Meier Block family near a very rural 126th Street and Gray Road. The Block farm was essentially where Brookshire subdivision and golf course are now located. Far back from Gray Road stood the supposedly haunted Block Mansion. Kids liked to go there just to try to scare each other. It was especially effective on a dark, windy night. Today, owner’s liability and trespass laws would prohibit any thought of such activity. In the 50s no one seemed to worry about it.

Then, there was Northwood. It was a hangout for teens from Carmel and from a new, prestigious North Central. Northwood had started as a truck stop in the early days, but found its niche as a drive-in restaurant. It was located at 91st Street and U.S. 31 which is not Carmel, but close enough to visit without raising parents’ concerns. Northwood served its sandwiches on toast instead of buns. Before going to Northwood, one might have to get gas at John Parsley’s Standard Station which did business in a way hard for us to imagine today. Not only was gas 29 cents a gallon as late as 1959, but you didn’t have to pay immediately. John would pump your gas, check the oil and then just wave as he said, “I got ya.” That meant he would remember to record the amount, and you could pay at the end of the month. John trusted you to come back, and you trusted him to charge the correct amount. That was John Parsley, and that’s the kind of place Carmel was in the 1950s.