Think you know everything there is to know about Jane Goodall? Think again. We know she’s the British scientist who spent most of her adult life observing chimpanzees in Africa. We know her findings introduced the world to a previously elusive species of primate, and in the process, helped solidify Darwin’s theory of evolution. We’ve all studied her work in class, and seen countless PBS documentaries about her. I wondered why director Brett Morgen felt the need to offer up a big screen documentary about such a well-known and widely respected subject.

Several phenomena conspire to make “Jane” this year’s best documentary. First, Goodall’s late husband Hugo van Lawick was a photographer and one of the premier wildlife filmmakers in history. His never-before-seen footage of Goodall and her work ended up in Morgen’s hands. Morgen asked Goodall to describe each scene, and the result is a narrator-less peek into not only her work but also her family life. Goodall’s astute observations of her own life parallel her 1960s observations of the Tanzanian chimps. By allowing Goodall to narrate her own story, Morgen has removed the most common (and often most distracting) facet of the typical National Geographic broadcast – the unseen voice announcing everything we’re seeing. He lets Goodall herself be that voice, and she treats herself as somewhat of a scientific subject.

Second, “Jane” is as much about Goodall as it is her furry subjects. I didn’t even know Goodall was married, let alone had a son. Goodall and van Lawick met when he was assigned to cover her work. They married in England then returned to Africa. Their son’s early life was spent in the Tanzanian chimp camp with her, and on the Serengeti with him. The inclusion of this footage (and corresponding observatory voice-over by Goodall) serves to humanize her. She’s no longer some awkward Brainiac who prefers the company of other primates to humans. Morgen exposes her as a curious truth-seeker who had always dreamed of performing the exact work for which she is known.

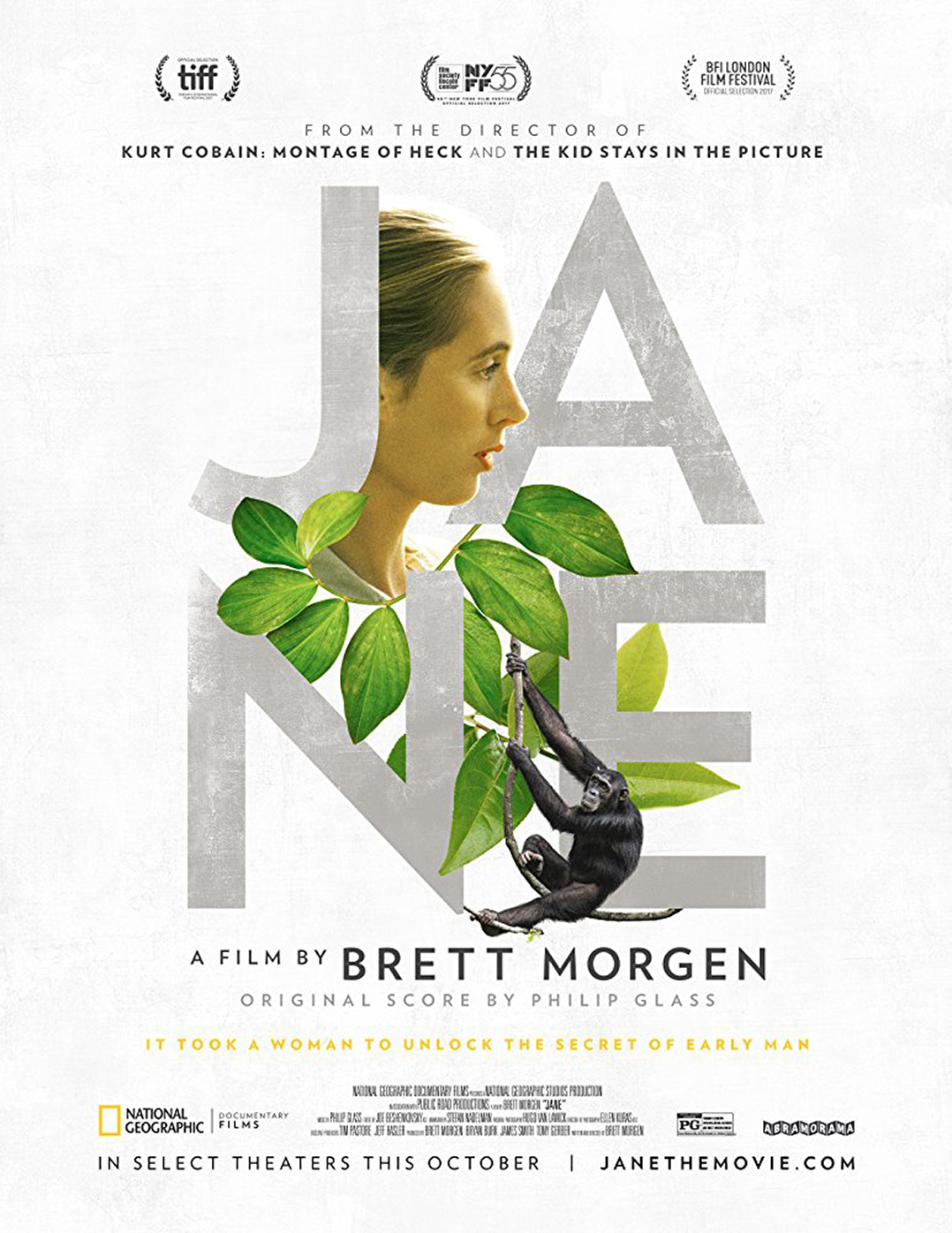

As Goodall’s voice is devoid of wild swings of inflection, Morgen accentuates her words with the brilliant musical score of American composer Philip Glass. At first annoying due it its mere presence, the Glass score serves to move our emotions in the same direction as Goodall’s. Where her staid tone might cause us to miss some grand pronouncement of primate behavior discovery, Glass provides the proverbial exclamation point.

Finally, “Jane” ultimately succeeds on the merits of Goodall’s body of work. By now, we all know that she gave each of the chimps names and charted their family trees. We know that her discovery of the chimps’ ability to manufacture and use tools was groundbreaking, but we may have forgotten just how severely that discovery caused the walls of the scientific community to shudder. One scientist proclaimed that we would now be forced to redefine man, or consider chimpanzees humans.

Much of what we learn in “Jane” was heretofore unknown by the masses. Did you know Goodall is not a scientist and had no formal training when Dr. Richard Leakey chose her for on-site chimpanzee study? Were you aware that chimps suffer depression just as do humans? Did you know that chimps engage in what could best be described as war? Clan versus clan. To the death.

There’s a lot of information gently compressed into “Jane’s” 90-minute running time. You won’t realize how much you’ve learned until long after the closing credits have rolled. But more than simply expanding our wealth of knowledge, “Jane” succeeds at something few films are capable of – it takes us on a journey of discovery. It exposes the far reaches of human possibility – the way Ron Howard did in 1994 with “Apollo 13.” This puts “Jane” in very rare company. And to think the only voice we hear is Goodall’s well-meaning monotone is a testament to a brilliant yet understated picture that perfectly captures the human spirit – and that of the chimps.