Cindy Klebusch recently bought a house in Indianapolis, and she’s not happy about it.

The 18-year resident of Carmel’s Meridian Suburban knew the aging neighborhood along Meridian Street likely would be purchased by a developer at some point, and now that it’s happened to make way for the Franciscan Health Orthopedic Center of Excellence, she said she and many of her neighbors can’t afford to stay in their hometown.

“We couldn’t go out and get the same kind of house in Carmel,” she said.

It’s not just Meridian Suburban residents who are concerned about being able to afford to continue living in a city they love. Some apartment dwellers and residents of Carmel’s older neighborhoods worry they’ll be priced out of their hometown as upgrades and redevelopment drive prices and assessed values higher.

Jennifer Miller, who served as executive director of Hamilton County housing nonprofit HAND Inc. until late 2019, said the fears are not unfounded.

“Anytime you lose an older housing stock, you lose a price point in a community that provides a housing opportunity for that young family or new professional who’s just trying to get their foot in the door,” Milller said. “It’s a common practice, it’s gentrification, and it’s a loss of attainable housing in a community.”

Carmel Mayor Jim Brainard said the city never uses eminent domain to obtain single-family dwellings for redevelopment projects, and he pointed out that anyone who sold a home in Carmel – including the Meridian Suburban residents – were not forced to do so.

Yet, he has acknowledged that Carmel does need more affordable housing options, and he’s working to draft an ordinance that will begin to address the problem. He’s proposing that a certain percentage of homes in new, single-family residential developments include an accessory dwelling, a self-contained apartment or small residential unit on the same property as the main structure.

Brainard said accessory dwellings were popular in the first half of the 1900s and were successful in diversifying the economic makeup of an area.

“It’s important we build affordable housing not to segregate the people who need affordable housing in barrack-like apartments,” Brainard said. “When people from different backgrounds and different economic strata interact with each other on a daily basis, that’s what forms communities. That’s why small towns work, because the fellow who is the physician or woman who is the dentist may be living in the same area as the guy who works in the factory.”

‘Nobody’s listening’

While an accessory dwelling may be a good fit for an aging relative or recent college graduate, it may not be the best solution for families needing an affordable place to live.

Sarah Frizzell and her husband, Jerry, have lived in Carmel for more than 15 years, welcoming two sons to the family during that time. They lived in the Mohawk Hills apartments until 2015, when new owner Buckingham Companies changed the name to Gramercy and made major renovations and increased rent prices, she said.

So, the family moved to Carmel Woods on North Range Line Road, but three years later they’re experiencing déjà vu. Barratt Asset Management bought the complex in early 2019, made upgrades and raised rents, Frizzell said. Her family worked out a deal to allow them to stay for another year, but she’s unsure where they will live after that.

Like Klebusch, she has no desire to leave her longtime hometown.

“It’s surprising and it’s sad, because we want to stay,” she said. “I think Brainard and everybody else could help with that, but right now either nobody’s listening or cares about it.”

It’s families that are most affected, Frizzell said.

“Most of the ones that are moving and staying in Carmel are single people or the ones that don’t have any kids, because it’s cheaper,” she said. “They get a studio or one-bedroom apartment, but everybody that has a family is moving out of Carmel because they can’t afford it.”

There is no shortage of apartments in Carmel, with hundreds more under construction or part of developments set to open in the coming years. While most are marketed as “luxury” units, Brainard said the sheer volume helps drive down rents.

“Just think of what the prices would be if there weren’t any new apartments being built,” Brainard said, adding that 25 years ago it was rare to see new apartments approved for construction in Carmel. “If you account for inflation, prices have come down. That’s because of the supply.”

According to George Tikijian, executive managing director at Cushman & Wakefield, the average rental rate of a Carmel apartment was $609 in 1994. When adjusted for inflation, that equates to $1,070 in December 2019, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Carmel apartment rents were the third-highest in the state at the end of 2019 at $1,199 average per month, according to data compiled by apartment search website RENTCafé. That is an increase of $66 from the previous year. Nationwide, apartment rents increased by $43 in 2019.

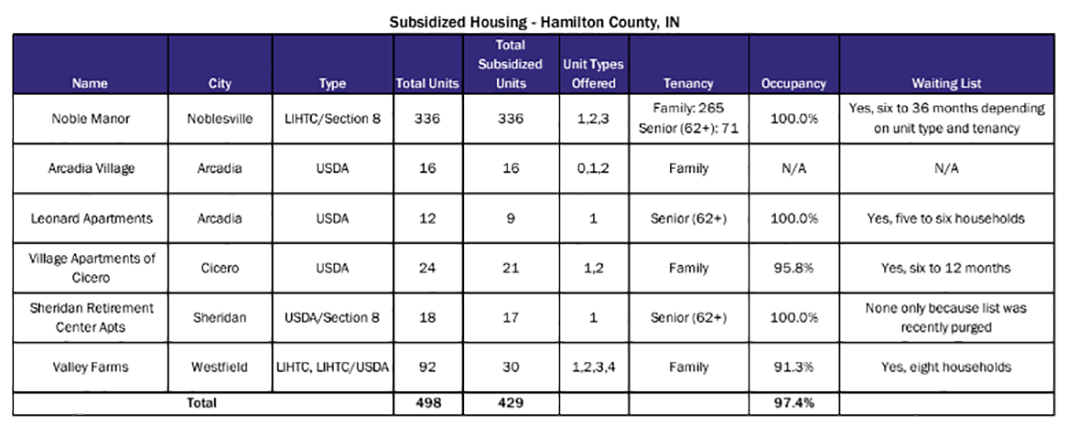

According to a Housing Needs Assessment released in 2019 by HAND, approximately 7.7 percent of rental units in the county are subsidized or affordable, although 67 percent of renter households in the county are eligible for those types of units. The report notes that very few of those units are in Carmel, and if they were evenly distributed per capita throughout the county, Carmel would gain 593.

Brainard said there are programs, such as Federal Housing Administration loans, available to help families like the Frizzells if they are willing to consider home ownership.

But Frizzell said that’s not a realistic option for her family.

“The amount per month would be way too much for us to pay, because Carmel is so expensive,” Frizzell said. “Our Realtor even said that it is way too expensive, and we wouldn’t be able to get anything in Carmel.”

‘A target on our back’

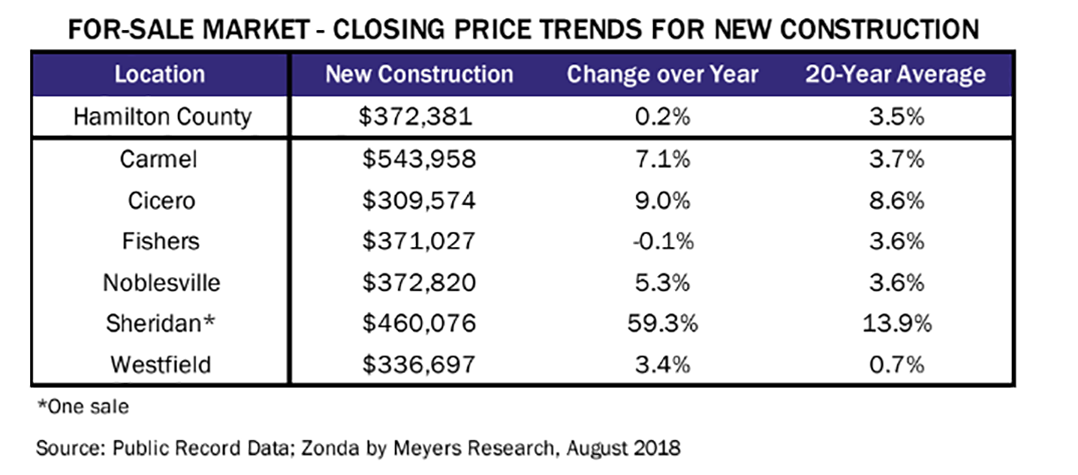

Elsewhere in Carmel, neighborhoods are transforming a bit slower than Meridian Suburban, especially near the Arts & Design District and Midtown. The areas are home to some of Carmel’s oldest neighborhoods, and in some – such as Newark Village and Auman Addition – new, expensive homes frequently replace much smaller ones.

On the other side of downtown Carmel, most of the original homes in the Johnson Addition and Wilson Village neighborhoods are still standing, but residents worry they won’t stay that way for long.

Developers recently withdrew plans to convert a single-family home into four townhomes at the entrance of the Johnson Addition neighborhood, but Charlie Demler, a nearly 40-year resident of the area, said he expects the higher-density proposals to keep coming. He said he and his neighbors frequently receive calls and letters from developers seeking to purchase their homes.

“Me and my neighbors feel we’ve got a target on our back now,” said Demler, who serves as the neighborhoods’ Crimewatch block captain and runs a Facebook page for Johnson Addition, which doesn’t have a homeowner’s association.

Demler said one of his neighbors listed his home for $300,000 and had interested buyers but decided to take his home off the market after he realized he wouldn’t be able to find a similar home in Carmel he could afford.

“I don’t think there is such a thing (as a reasonably priced home) in Carmel,” Demler said. “We know our homes are going to get bought up eventually. They’re going to be made bigger and they’re going to cost a lot more.”

A beautiful problem

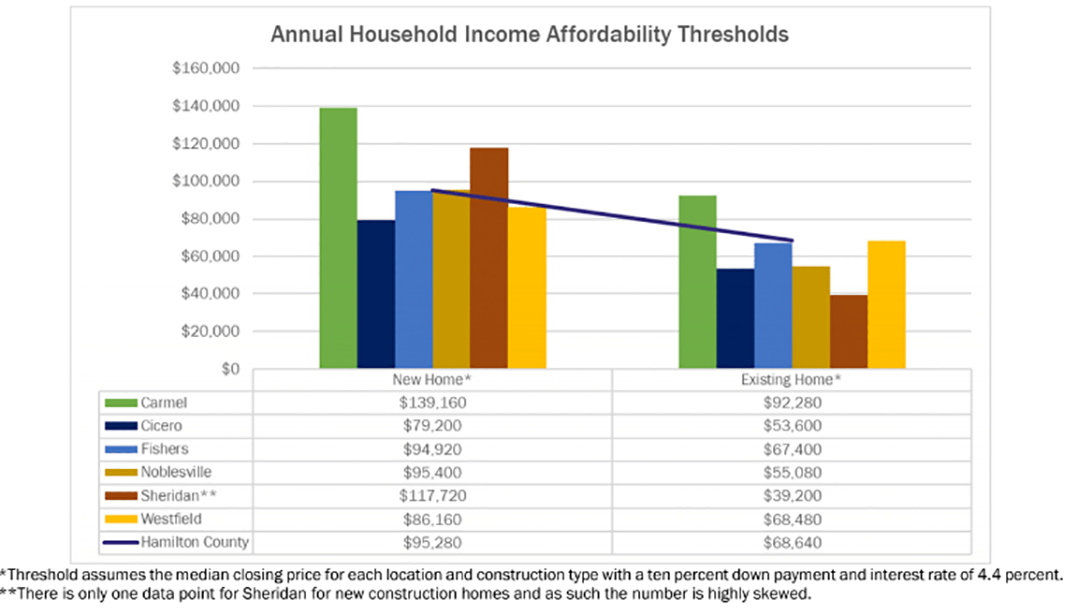

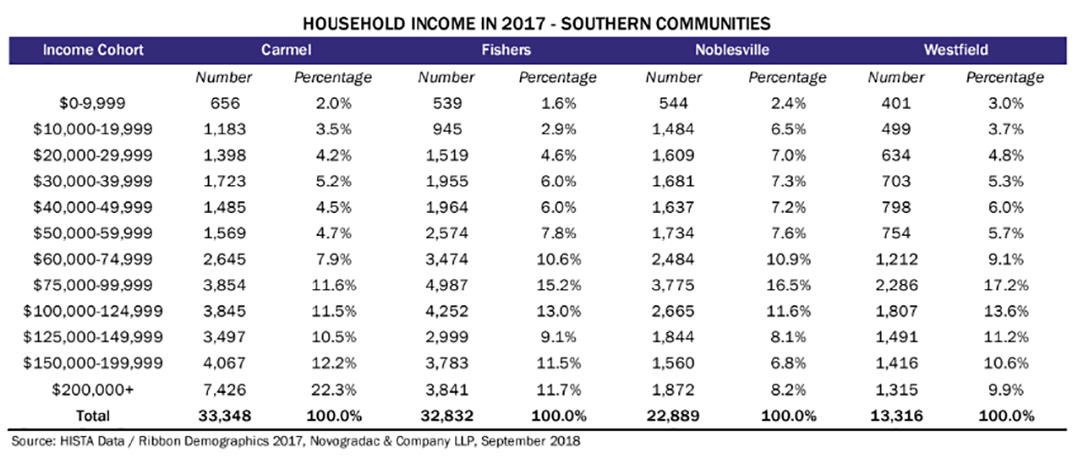

Shell Barger, a Realtor with RE/MAX, said she often is unable to find affordable homes for clients who want to live in Carmel. She said a buyer must make about $50,000 a year to afford a $200,000 home and that they must make at least $85,000 a year to afford a $300,000 home. Average home prices in December 2019 in Carmel were nearly $470,000, and at the time of the interview she found only six homes in Carmel listed for less than $200,000 and none listed for less than $175,000.

“One of the affordability problems has made Carmel beautiful and a desirable place to live, but we displaced those people,” Barger said.

One of the most visible effects of a lack of affordable housing is in many of Carmel’s service industries. Many businesses are having a hard time finding and keeping workers on the low end of the pay scale, as those employees – who may not have reliable transportation – can find similar jobs closer to home.

“There’s a big gap between how employees are paid in those sorts of service-industry jobs and our expectations as consumers for having quality service,” said Justin Moffett, a developer and founder of Old Town Companies, which has built many of the new homes in Carmel’s older neighborhoods. “We’re kidding ourselves as citizens of Carmel and consumers if we don’t care about affordable housing and we expect to have quality service when our mom or dad are being cared for in a nursing home or hospital, or even a restaurant for that matter.”

Moffett said the problem doesn’t have an easy solution, but he believes communities throughout Hamilton County must work together to address it.

“We intellectually acknowledge it’s a need, but no one really wants to deal with the problem,” he said. “That’s why I think it’s a countywide discussion.”

Old Town to ‘test run’ affordable housing

For developer Justin Moffett, business has been good of late. His Old Town Companies have built many of the new, larger homes in Carmel’s aging neighborhoods.

“We are not apologetic about the fact that we serve consumer demand. Any business does,” he said.

At the same time, Old Town has attempted to be philanthropic with its earnings. Through The Orchard Project, it manages properties for families in crisis and contributes to help build a home in a developing nation for every home it builds locally. But Moffett said he’d like to do more by finding a way to incorporate affordable housing in Old Town’s new developments.

Old Town is making its first foray into offering affordable housing as part of North End, a mixed-use development on 27 acres near Smokey Row Road and U.S. 31. Approximately 20 percent of the multifamily units will be subsidized and set aside for adults with intellectual developmental disabilities thanks to a the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority’s Moving Forward program, which selected Old Town as one of two developers to receive funding and support in 2020 to develop affordable housing.

“This is something we endeavored to do in our North End development as a test run,” Moffett said. “There’s no lack of willingness. If we could figure out how to make an affordable component in every development, we would.”

While Old Town would like to incorporate affordable housing in its other developments, the cost of land and city’s high architectural standards make it nearly impossible, Moffett said.

“It’s pretty amazing what the expectations are from surrounding property owners and our planning officials for quality standards,” Moffett said. “I’m not providing a criticism, but people don’t want anything less than what they have as a standard for what goes next to them.”