The danger was all too familiar for Sharif and Tim Siddiq.

With the Taliban gaining control of Afghanistan in August only days after the U.S. withdrew its troops, the brothers, born in the U.S. Embassy hospital in Kabul, knew that many of their relatives and friends were in grave danger, either because they had supported the U.S.-backed government or could be connected to someone who did.

So, Tim got to work, petitioning state leaders to use their political ties to help his family find a way out. His relatives weren’t given much hope for evacuation from those on the ground looking to secure their escape, but Tim never lost heart.

“All of them were telling (my relatives), ‘You’ve got a 1 percent chance we’re going to get you guys out,’ but I said, ‘It’s 100 percent,’” Tim said. “God has always protected our family.”

The wait wasn’t easy, and Tim, an Indianapolis resident and father of five, ended up in the hospital because of the stress, induced by an evacuation deadline and navigating through thousands of documents and emails that included everything from threats to pleas for help. But he was proven right. On Oct. 20, more than 20 of his family members secured a flight to Qatar, thanks to the compassion of the nation’s foreign minister, Tim said, where they are living until space opens up for them in a refugee camp in the U.S.

The brothers were relieved, much as they were the first time their family fled Afghanistan in 1979.

Fleeing from home

Sharif, a Carmel resident and father of two, said he and his brother enjoyed a happy childhood in Afghanistan. They have fond memories of flying kites in their spare time and exploring as their mother worked on plein air paintings in some of the nation’s most beautiful settings.

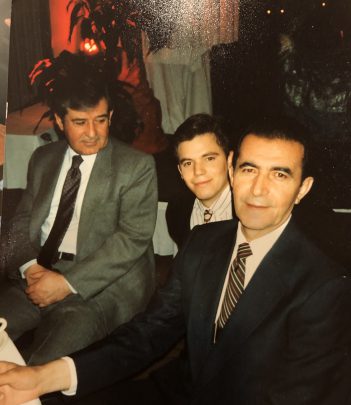

Their parents had met at Indiana University, where their father, Mir Siddiq, was pursuing a doctorate in education administration and their mother, Patricia Foley Siddiq, was working on a master’s degree in art education. The couple married and moved to Afghanistan, where they welcomed three sons. Mir worked in the nation’s ministry of education from 1966 to 1978, becoming Afghanistan’s acting minister of education in 1973 in the cabinet of President Mohammed Daoud Khan.

The brothers will never forget the day their idyllic life crashed to a halt in late April 1978. They were playing outside when two jets flew overhead so low and fast that a sonic boom busted out glass in their home. They spent the rest of the night barricaded inside, an armed servant guarding the door, listening to the sound of machine gun fire, mortar rounds and helicopters. The Saur Revolution had begun, and within hours the president and his entire family were dead.

This was bad news for Mir, whose political ties made him a target of the insurgents. But for some reason — Tim thinks it’s because his father was married to an American — Mir was the only non-Communist former cabinet member not to be executed. Instead, he was put on house arrest, and in 1979, U.S. Sen. Richard Lugar helped him secure a spot on the last flight out of Kabul before the Soviet invasion. He joined the rest of his family, which had been evacuated several months earlier, in Indiana, eventually settling in a Brown County farmhouse and becoming an active member of the community.

But in 1992, a recently divorced Mir surprised his family and decided to return to Kabul, where he worked in the administration of Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah.

“He always had a desire to go back and help the people of Afghanistan,” Sharif said. “He had a prominent position in Afghanistan. A lot of people looked up to him, and he felt like he wasn’t able to help them from here.”

Much to their dismay, Sharif and Tim never saw their father again. He died of natural causes in 2001 after additional political unrest led him to flee in 1996 to Pakistan. He is buried approximately 1 mile from where Osama bin Laden would later be killed.

Being their voice

More than 40 years after the Siddiq family first fled Afghanistan, it became clear that their relatives remaining there would need to follow suit.

Almost as soon as the Taliban regained control of the nation in August, life began to change. Tim said his college-educated female relatives were told they could no longer work, and other family members were threatened, beaten or had property stolen. Sharif and Tim feared their relatives’ lives were in danger.

Tim, president and CEO of Indianapolis-based freezer warehouse MW Cold, has long been interested in politics and through the years had made connections with several Hoosier elected officials. He is especially close with Attorney General Todd Rokita, a fishing buddy, and he reached out to see what Rokita could do.

While coordinating evacuations is not typically part of the attorney general’s job description, Rokita felt compelled to help, especially since he felt the federal government wasn’t doing enough to evacuate Afghan allies in harm’s way. He connected the Siddiq family with officials in Qatar, sent an official letter asking for help and worked to assist where he could.

“I had a chance to leverage various relationships, inside the state, outside the state and outside the country,” Rokita said. “We kept pressing and pressing and pressing, and it worked. There were times we thought there’s no way in hell (it would happen), based on what we were hearing on the news, but it’s an example of persistence and how God helps people who help themselves.”

The Saddiq’s have a lengthy list of friends and connections in Afghanistan they still hope to evacuate, and others with ties to the nation have reached out to Tim to see if he can help. He’s always willing to try.

“I have to, because they have to have a voice here, somebody that can fight for them,” he said.

A new home

Sharif and Tim Siddiq are not the only employees at MW Cold, a freezer warehouse in Indianapolis, forced to flee their home nation.

Mukhtar Ibrahim began working there as a teen in 2008, not long after moving to the U.S. Born in Somalia, his family became refugees in the 1990s as the nation experienced civil war. He lived in several nations before spending 10 years in Syria awaiting a permanent new home.

The Catholic Church helped relocate his family to Indiana in 2007 and led him to his first job as a sanitation worker for MW Cold. Ibrahim, an Indianapolis resident, worked his way up through the years and is now the warehouse supervisor for the company.

Ibrahim, who became a U.S. citizen five years ago, said growing up on the move helped him develop a unique perspective.

“I’ve been to seven or eight different countries and been treated in different ways,” Ibrahim said. “Give everybody chances to prove themselves. That will help a lot of people in many walks of life.”