Jim Brainard admits he didn’t know much about city planning when he won his first Republican primary in 1995 for Carmel mayor. Without a Democratic challenger in the general election, the career attorney had seven months to study the topic before taking office.

Thus began a journey of contacting urban planning experts and gathering every resource on the topic he could find. He made copies of university-level class syllabi and read the books most often referenced in their bibliographies.

Nearly three decades later, as Carmel has grown from a standard first-ring suburb to an internationally recognized model of new urbanism, the tables have turned. Now, city planning experts are coming to Brainard for advice, and he’s more than willing to share the secrets of his success.

“Don’t be afraid to do bold, innovative things, and read and read and read,” he said. “Bring in the best consultants. Read everything you can about city planning, constantly. I spent at least six hours a week for 28 years reading city planning journals and books.”

Jeff Speck, a renowned city planner and author, is one such expert Brainard has consulted frequently over the years.

“Mayor Brainard is an urban design junkie, which is not a bad thing to be in his position,” Speck said. “I’ve worked with him over two decades and it’s been a delight, because he actually teaches me stuff. But he also is a good listener and is willing to try something new.”

Ron Carter joined the Carmel City Council the same year Brainard became mayor, serving in the role for 24 years. He said Brainard purchased cases of books on city planning to distribute to other leaders in the early days and was stunned by the mayor’s ability to convince some of the world’s leading experts to consult in Carmel, such as the late David Oliver, who worked closely with England’s then-Prince Charles on sustainable design. During visits to Indiana, Oliver provided feedback and suggestions on the planning of Carmel City Center.

“It’s been a great ride,” Carter said. “What (Brainard) has accomplished has been unparalleled in the state of Indiana and in many cities around the country. No one can say that they’ve accomplished what he has and in the way it’s been accomplished.”

Creating a walkable city

Among Brainard’s proudest feats is the creation of a walkable urban core – centered around a railroad turned greenway – that stretches from the Arts & Design District through Midtown to Carmel City Center. He said this became a priority even before voters elected him mayor.

“I knocked on lots of doors to win that first election and asked people what their hopes and dreams and aspirations were for the place they had chosen to raise their families and start their businesses and work and live, and I heard, ‘I wish we had a downtown. I wish there’s a place to show people that visit from out of town. I wish I didn’t have to drive all the way to downtown Indy for dinner and a show,’” he said. “It was this yearning for a traditional, walkable city.”

Carter remembers a conversation with Brainard after one of their first city council meetings in 1996 when he said the mayor asked him what he envisioned for the area north of Carmel City Hall up to Main Street. Carter said he suggested park space, but Brainard was already dreaming bigger.

“What he had in mind was what you see today, and it has far exceeded what I couldn’t envision,” Carter said. “As he went along, and as I could see what he was doing, it was very easy for me to get on board.”

Several years later, Brainard reconnected with Bruce Cordingley, co-founder of development firm Pedcor, when Cordingley called to ask some questions about relocating his business to Carmel. The two had met years earlier through a mutual acquaintance and had both worked as attorneys on a potential hotel development.

Brainard shared with Cordingley his vision for creating a downtown area for Carmel, which led to Pedcor joining the city in a public private partnership that is still going strong 20 years later. Pedcor helped develop an empty field at Range Line Road and 126th Street into Carmel City Center, which includes apartments, restaurants, green space, the Center for the Performing Arts and Hotel Carmichael. The final buildings are still under construction.

“We always saw it as a long-term partnership, not just to do a particular building or development and then you’re done,” said Cordingley, whose company is set to continue its work in Carmel beyond the Brainard era through a $700 million mixed-use project at 111th and Pennsylvania streets.

Carmel City Center is home to the Palladium, a concert hall that Brainard counts among his top accomplishments as mayor. He said he decided to anchor Carmel’s downtown with a performing arts campus to differentiate the city from its neighbors who were working to draw visitors for sports or other types of attractions.

“I thought, ‘That’s a perfect niche for us to drive people to our new downtown.’ We’ll do it with arts and art-related festivals,” said Brainard, the son of two musicians and a French horn player himself. “And it has worked.”

In recent years, Brainard and his team have worked with other private developers to transform an aging industrial area north of Carmel City Center into Midtown, which features new mixed-use buildings bisected by Monon Boulevard and the revamped Monon Greenway.

For this project, Brainard once again turned to Speck for design help. The mayor had already rejected two plans for the area and encouraged Speck to take a look at it.

Speck said the mayor embraced his “crazy idea” to surround a recreational trail with roadways and credits Brainard with having the vision to completely transform and connect Carmel’s core.

“(Carmel City Center) didn’t exist when Mayor Brainard took office, and Main Street was not worth a visit. He made those places what they are,” Speck said. “Then he noticed that nobody walked between these two walkable locations except people trying to burn calories, so he focused on their connection, which became Monon Boulevard. Carmel now has a walkable downtown that stretches more than half a mile. That’s a heck of a legacy to leave behind.”

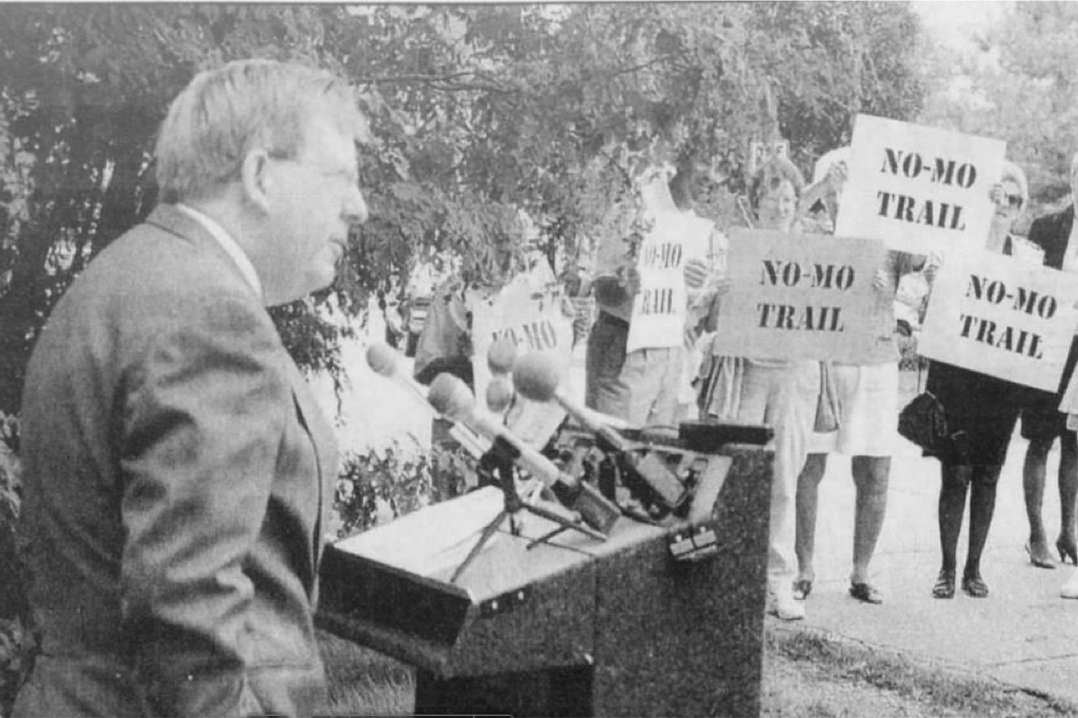

Facing the critics

Building a city center and world-class amenities hasn’t come cheap. Several projects, including the Palladium and Hotel Carmichael, cost significantly more than initial estimates, and Brainard has faced criticism of methods he used to make up the difference and for the city’s overall debt load. He’s also been through 56 annexations, with the last one – the annexation of Home Place – delayed by a multi-year court battle.

He’s faced pushback from some of his supporters, too. Carter, who described Brainard as having “a lot of patience,” said he avoided confronting the mayor during public meetings or events, but he wasn’t afraid to challenge him in other settings.

“He was really tolerant of me from the standpoint that I would really get in his face in his office,” Carter said. “People said on many occasions that I was the only one that would tell the mayor what he needed to hear, not what he wanted to hear.”

Brainard handled public criticism well, too, Carter said.

“(He has an) ability to withstand the slings and arrows of people who had different ideas about what the community should do or shouldn’t do,” Carter said. “When we were first in office, there was a great deal of resentment because people saw what they thought was old Carmel going away. But communities always change. You either move forward, or you move backward, you don’t stay the same. In his case, he always felt that moving forward was the way to go.”

Brainard said that he is a strong believer in continuing to work and build relationships with people or groups that don’t always align with his way of thinking.

“It doesn’t mean you’re weak, simply because you talk to somebody. It takes a bit more strength to do that. It’s easy to just shut them out,” he said. “But we need to talk and look for areas of agreement, and if you’re not going to have agreement, at least an understanding of why they’re making the decisions they are. In the best of worlds, that can lead to resolutions.”

Roundabout inspiration

Beyond Carmel’s city limits, Brainard is perhaps best known for transforming the city into the Roundabout Capital of the U.S. The city didn’t have a single roundabout when he took office, but as he prepares to step down, it’s difficult to find a major intersection without one.

It all began with a forgotten toothbrush.

Brainard was visiting an Atlanta suburb in the mid-1990s to attend a wedding when he realized he’d left the important hygiene item at home. So, he hopped in the car for a quick trip to purchase a new one, but it was rush hour and the simple errand took an hour and a half, he said.

“I could have walked there three times in that amount of time. I (wondered) how do we avoid this sort of thing?” Brainard said. “I had been lucky enough to do a bit of my grad school in England and I’d seen modern roundabouts they were using there. Just from observation, I knew that they worked better.”

So, Brainard began learning everything he could about roundabouts and began working to convince local planners – and residents – that it would be worth investing in them in Carmel. It wasn’t easy, at first, and there was a bit of a learning curve.

Brainard brought roundabout expert Peter Doctors to the city for help when he realized that more fender benders were occurring in the redesigned intersections than expected.

“(Doctors) looked at them and said we needed to adjust the angles,” Brainard said. “So, after the first six months or so he recommended some changes. They weren’t expensive changes, but those were our first (roundabouts) and we didn’t know how to do them yet.”

Now, Carmel has 150 roundabouts of various shapes and sizes, from micro-roundabouts in neighborhoods to grade separated, oblong ones along Keystone Parkway and Meridian Street that made traveling the city’s two major north-south thoroughfares much more efficient. The roundabouts are credited with reducing injury accidents in the city by 80 percent and reducing fuel use and emissions.

Speck said he is impressed with Brainard’s transformation of the city’s intersections.

“Carmel is a driving suburb, and Mayor Brainard has answered the question of how to make such a place the best it can be,” Speck said. “His 150 roundabouts have reduced crashes in a major way; he has saved lives. And his ‘peanut-about’ plan for Keystone Avenue allowed that highway to stay at four lanes rather than being expanded to six, saving a ton of space, asphalt, and fuel. It’s remarkable.”

Many of the roundabouts have become 360-degree galleries for public art. Artist Arlon Bayliss has designed eight of Carmel’s roundabout sculptures, with one yet to be installed along 96th Street to complete a series of four pieces that pay homage to historic Indiana carmakers in an area now home to several car dealerships.

Bayliss said the mayor wanted to do “something different” in the area to create an attractive corridor for existing and future businesses.

“That expansive vision makes it unlike any other corridor in the nation,” Bayliss said. “It’s got unique beauty with an Indiana story to tell. For me, that’s truly transformative.”

What’s next?

When Brainard first took office, he planned to run for reelection one time and then go back to his work as an attorney. But every four years he would be encouraged to run again and felt there were too many projects in the works to step away.

Eventually, he concluded there would be no perfect time to retire from elected office.

“I realized I could be 98 years old and still have a list of projects that I’d like to take up later,” he said. “So, I took that out of the analysis and thought, ‘Did we accomplish what we set out to do?’ And the answer to that is yes, we far exceeded what we thought we could ever do.”

Many of the mayor’s visions turned into reality, but some never materialized. Many years ago, he began working on a plan to build a manmade lake with a swim beach – think a smaller Geist Reservoir – near the area where Central Park is now, but he realized it would be near impossible to aggregate the 1,000 acres or more needed.

“I wish, maybe if we would have worked at it a little harder, we would’ve done that,” he said.

Brainard said he isn’t ready to announce what’s next for him until January 2024, when he is officially retired from political office and his successor, Sue Finkam, is officially sworn in.

Carter ended his time on the city council at the end of 2019, and he is thankful that he served alongside Brainard the entire time, as the city’s population more than doubled and it topped ranking after ranking of best places to live.

“He was the right person at the right time for Carmel,” Carter said.

State of the City address

Carmel Mayor Jim Brainard will present his final State of the City address at 5 p.m. Dec. 4 at the Palladium, 1 Carter Green. Tickets for the event, which is presented by OneZone, are $40 and may be purchased at thecenterpresents.org/tickets-events/events/2324/rental/state-of-the-city.

Timeline of Mayor Brainard’s time in office

- 1995 – Defeats incumbent Ted Johnson in primary

- 1997 – 96th Street bridge opens over White River

- 1997 – First roundabout constructed in Carmel

- 2002 – Monon Trail opens from 96th to 146th streets

- 2003 – City completes its largest annexation

- 2003 – Defeats Luci Snyder and Wayne Wilson in primary, defeats H. Dean Barkley, Jr. (L) in general election

- 2005 – Arts & Design District gateway unveiling

- 2006 – Carmel City Center breaks ground

- 2007 – Defeats John R. Koven in primary, defeats Henry Winckler (D) and Marnin J. Spigelman (I) in general election

- 2007 – Brainard and Gov. Mitch Daniels announce agreement to transfer ownership of Keystone Avenue to the City of Carmel

- 2008 – Reconstruction/reconfiguration of Keystone Avenue begins

- 2009 – Brainard named “Elected Official of the Year” by the Hoosier Environmental Council

- 2010 – Carmel annexes Southwest Clay

- 2011 – Defeats John V. Accetturo and Marnin J. Spigelman in primary

- 2011 – The Palladium, Studio Theater and Tarkington Theater open at the Center for the Performing Arts

- 2015 – Defeats Rick Sharp in primary

- 2018 – Carmel annexes Home Place

- 2019 – Defeats Fred Glynn in primary

- 2019 – Midtown Plaza opens

- 2020 – Leads city through COVID-19 pandemic

- 2022 – Announces retirement from political office

- 2023 – City’s 150th roundabout complete

- 2023 – Final term ends Dec. 31

- ANOTHER SIDEBAR

- Thoughts on Mayor Brainard

Thoughts on Mayor Brainard

“When I graduated from Carmel High School in 1990, Carmel was a small city of 25,000 people. The population boom here over the last 30 years can be directly attributed to the vision of Mayor Brainard. Carmel has transformed into one of the most highly regarded cities in America for its low taxes, its top-tier infrastructure, its safety, and its amenities. There’s no Mt. Rushmore for mayors, but if there were, Carmel could make a compelling case that Jim Brainard’s face should be up there.” – U.S. Sen. Todd Young

“Having been elected to the general assembly just a year after Mayor Brainard was elected mayor, I’ve had a front row seat to his leadership and vision as he led the transformation of Carmel into the beautiful city that it is today. What he has accomplished here has been nothing short of remarkable. I wish him all the best in his future endeavors after his term ends at the end of the year.” – State Rep. Jerry Torr

“He was a breath of fresh air in the community, because he wasn’t thinking in the way that old Carmel thought. He was thinking about what the city could be. He has done a good job of achieving his vision.” – Ron Carter, Carmel City Councilor from 1996 to 2019

“Good art needs good patronage, and (Mayor Brainard’s) courage and ambitious vision has led to me also being courageous.” – Sculptor Arlon Bayliss

“(Mayor Brainard) is a unique leader – transformational would be almost an understatement.” – Bruce Cordingley, president and CEO of Pedcor Companies